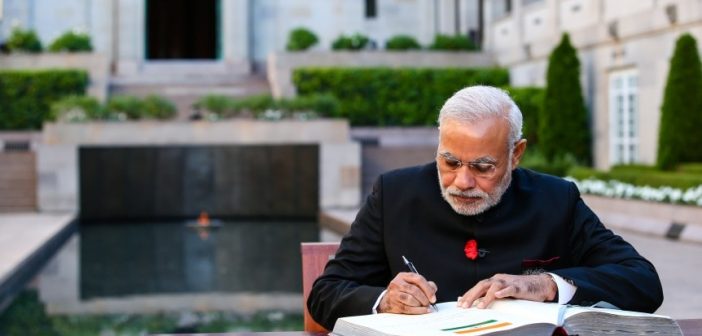

As the Indian Prime Minister launches critical reforms of India’s bureaucratic structures, foreign affairs and trade must go hand in hand, writes India Inc. Founder & CEO Manoj Ladwa.

To say that India’s bureaucracy is in need of reform would be an understatement. But no Indian Prime Minister has dared to shake up an institution that wields more power than most civil services anywhere in the world. Well, until now.

Prime Minister Modi has recognised that in order to catapult India into a $5-trillion economy – the world’s third-largest behind the US and China – in the next few years, he urgently needs a bureaucracy that is well resourced and filled with the right talent.

Inducting private sector domain specialists laterally into senior positions in the tradition and precedent-bound Indian bureaucracy is nothing short of revolutionary in the Indian context. It is set to be one of his most ambitious and boldest reform measures till date.

In April this year, after more than a year of debate, discussions and preparation, the government inducted the first batch of laterally recruited nine joint secretaries in the departments of Agriculture, Cooperatives & Farmers Welfare, Civil Aviation, Commerce, Economic Affairs, Environment, Forest & Climate Change, Financial Services, New & Renewable Energy, Road Transport & Highways and Shipping. Joint secretary is a senior bureaucratic position in India.

This can, potentially, become one of the most far-reaching reforms undertaken by Modi, if, as envisaged, the government goes ahead with its plan of recruiting more than 400 more domain specialists from the private sector into various departments of the government.

Generalists in specialist positions

The Indian Administrative Service (IAS) and the rest of the Indian bureaucracy is the successor to the British era Indian Civil Service (ICS), which had been set up by the erstwhile colonial administration to primarily maintain law and order and collect revenues from the districts. Since Independence, Civil Services in India (which include three categories – All India, Central and State), have been dealt with Articles 310, 311 and 312. Civil servants in India go through a highly competitive and merit-based process, which probably is one of the toughest to crack in the world.

Every year, the bright and young cadre civil servants embarks on a long career in which they are expected to take on a wide variety of roles – from the district to the central level. Due to the nature of their career path and the training provided, civil servants in India tend to be generalists. Until about recently, officers with no specialised knowledge were considered adequate to carry out their responsibilities. But as management and public administration became more complex – and emerged as specialist fields of knowledge and service – the lack of specialists in the Indian bureaucracy began to be felt.

Incidentally, the IAS, which was referred to as India’s “steel frame” by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel – India’s first Home Minister, has been adjudged, along with the rest of India’s generalist bureaucracy, as Asia’s most inefficient by the Political and Risk Consultancy, a Hong Kong-based a consulting firm specialising in strategic business information and analysis in Asia.

One reason for this could be the more than 20 per cent vacancy rate in the IAS cadre of about 6,500 officers – or more than 1,300 officers. The reason: insufficient training capacity at the institution mandated to train such officers. As India embarks on its aspirations to become a $5 trillion economy by 2025, it is imperative that this “steel frame” is well equipped to enable this growth.

Foreign affairs, trade could be focus areas

Nowhere, in my opinion, is this acute shortage of talent more visible than in India’s Foreign Office and the Commerce Ministry.

India has about 940 Indian Foreign Service (IFS) – the dedicated cadre for the Ministry of External Affairs. This is about the same size as the foreign service cadre of small countries such as Singapore and New Zealand. Even Australia has a diplomatic cadre comprising more than 6,000 officers.

Countries with economies and global interests comparable to India – such as the UK, Japan, US and China – have more than five to 10 times as many career diplomats. Such a small foreign service was justified in earlier times when India didn’t have many tangible global interests. But now, with an almost $3-trillion economy and economic and strategic interests in almost every continent, India clearly needs a much larger foreign service to do justice to its size.

And the likely expansion of India’s foreign service cadre will also provide the Indian government the opportunity to steer its foreign policy orientation away from legacy ideological fetters and drive India’s foreign relations towards a greater trade and investment focus through better coordination and perhaps even a joint venture with the Commerce Ministry.

Here, New Delhi can take a leaf out UK’s playbook and laterally hire globally experienced trade commissioners. For eg, as one of the reactions to the impending Brexit, UK Secretary of State for International Trade Dr Liam Fox recently launched a training scheme to recruit “UK’s talent pool of future negotiators, policy makers and Trade Commissioners”. It calls upon people of all ages and experiences to work with the UK government and includes international placements across the Department for International Trade’s 127 locations worldwide.

In this context, may I add that ‘India Global Business’ and I have long argued that India needs a Trade Representative, along the lines of the US, to deal with its multilateral and bilateral trade relationships. This could be a good time to induct a lateral entrant with experience in global trade negotiations.

The Modi government has made a good beginning on allowing lateral entry of professionals into the Indian bureaucracy. The coming years will show if this experiment is paying the desired dividends.